Battles are counted by the victors. The cultural ones too. We have had hundreds of books and movies about the Movida Madrileña, explaining its ups and downs: Alaska, Pedro Almodóvar, McNamara and company have made headlines every time it is time to talk about transgression, as if they had not been supported by television from the very first moment. And yet, the music that was danced to in most of the rest of Spain had nothing to do with stratospheric makeup and ‘La bola de cristal’, but with two guitars, a bass and drums.

Spanish rock had its moment of glory in the 80s and 90s as the antithesis of pop. Beyond Loquillos and Ramoncines, Spanish rockers did not want to copy the American classics and their look was that of a person you would change sidewalks if you saw them at night in a dark alley: tank top, long hair and punk attitude, although the lyrics spoke of love and hopelessness. If you didn’t live through that era and still believe that the epitome of modernity was the Pegamoides, here are eight Spanish rock songs that don’t necessarily define the bands, but explain the rage that in Spain flew underneath any media back then. Horns, kalimotxo and guitar playing!

‘Un ABC sin letras’ – Platero y tú

Fito Cabrales has dedicated his adulthood to sing coplas to ‘Soldadito marinero’ accompanied by the Fitipaldis, but in 1990 he released with his friends a small album of ten songs titled ‘Burrock & roll’ which opened with a declaration of intent. Fito was 24 years old and wanted to revolutionize music, making it clear that they were not like the others: “I have two fingers in front and I never use both / And I walk down the street with my bad reputation”. Ten years later, Platero y Tú’s farewell in the back and on the last page of a newspaper traumatized a whole generation that is still waiting for a reunion tour that will never come.

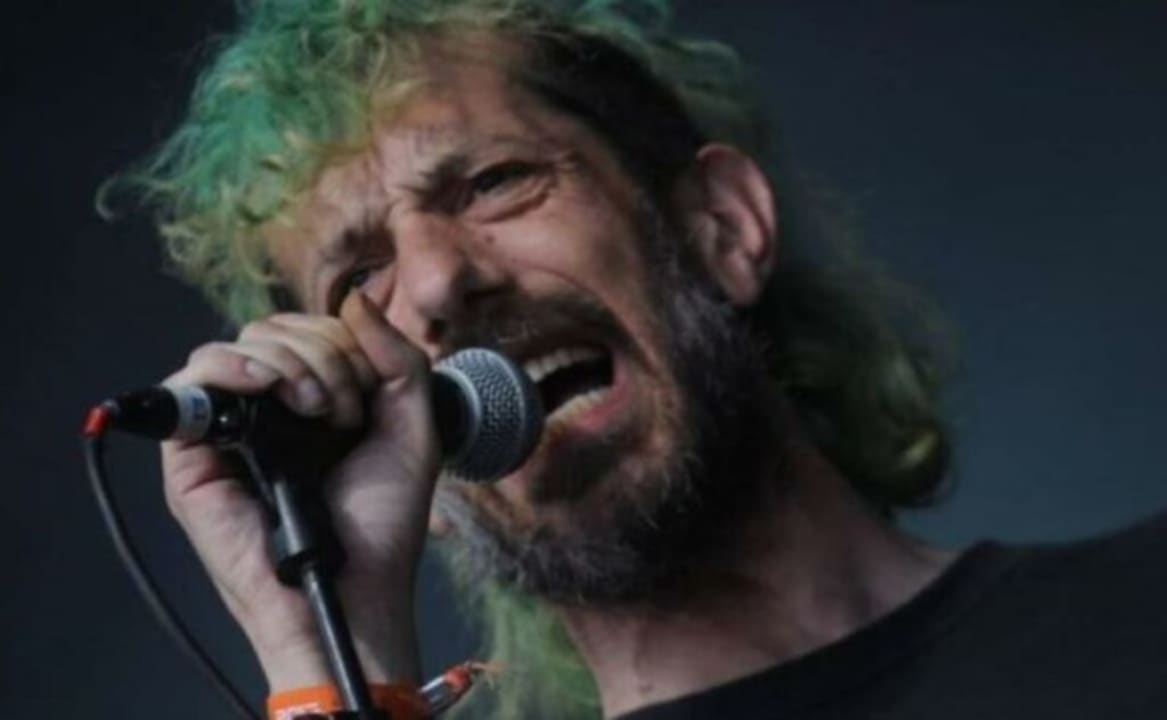

‘Estado policial’ – Extremoduro

Before Robe settled in and came his ‘Vereda de la puerta de atrás’ or his symphonic songs in ‘La ley innata’ and ‘Material defectuoso’, his first albums were downloads of rage that mixed heartbreak with sex, poetry or, why not, his attacks against authority. At the age of thirty and five years after founding Extremoduro, the group released their third LP, ‘Deltoya’, which, between hymns to harmony (‘Ama, ama, ama y ensancha el alma’) and truncated love songs like ‘Sol de invierno’, started with one of those songs that could never have been played in the movida: ‘Estado policial’ is the coarsest Extremoduro, the one that could only have come out in the underground of the 90s and who didn’t care about the consequences of their songs. Lyrics like “Pincho las arruedas de los coches policía, pongo un par de bombas en cada comisaría” (I puncture the tires of the police cars, I put a couple of bombs in every police station) still impress with their crudeness right now.

‘Barrio conflictivo’ – Barricada

Enrique Villareal, ‘El Drogas’ (better known today thanks to the meme in which he acknowledges having taken psychotropic substances) had just arrived from the military in his twenties and his life in Chantrea, the Pamplona neighborhood where fighting with the police, arrests, demonstrations and arrests were the daily bread, made him start a group to tell his reality. Barricada is, perhaps, the epitome of the Basque rock of the 80s and 90s, which in 1985 and under the production of Rosendo himself, created ‘Barrio conflictivo’, a song that with pure guitar told everything that nobody talked about. “Torture in interrogations. Aggressions, anguish and pain. Txantrea sinister nightmare, you are to blame for wanting to live in peace” marked the beginnings of a group that would never stop claiming social rights and the need to understand the past (before getting into internal brawls). A marvel.

‘Maneras de vivir’ – Leño

Since we have already mentioned him, Rosendo Mercado is the grandfather of Spanish rock, and that’s taking into account that the great majority of the groups moved in the upper part of the peninsula. In the center was La Movida, which he was not interested in at all. Maybe that’s why, among so much glam, he released with Leño ‘Este Madrid‘ (“Es una mierda este Madrid que ni las ratas pueden vivir”) as a prelude to the song that changed everything, the most important anthem of Spanish rock: ‘Maneras de vivir’. If when someone sings “No pienses que estoy muy triste” no contestas “Si no me ves sonreir” no podemos ser amigos. (“Don’t think I’m too sad” you don’t answer “If you don’t see me smile” we can’t be friends.)

‘El Congreso de Ratones’ – La Polla Records

Evaristo was 19 years old when he got on stage for the first time to sing his punk nonsense. La Polla Records fired for 24 years (and a small revival in 2019) against everything, including, of course, La Movida: the song ‘Herpes, talc and techno-pop’, as a substitute for the slogan “Sex, drugs and rock & roll”, gives a good account of it. However, in a dialogue with the present day, we have to choose ‘El Congreso de Ratones’, which in 1985 closed their second album, ‘Revolución’, and which years later would be covered by Estopa in some concerts, demonstrating that, deep down, we are nothing: “Camouflaging this fascism in democracy because here the same people always rule”. The day Gen Z discovers La Polla Records there will be some very strange dances in TikTok.

‘Aprendiendo a luchar’ – Reincidentes

Reincidentes was born out of pure chance and the student revolt in Seville, at a time when they felt that music was just another element of support to power and only singer-songwriters and some rock groups were able to be something more. Fernando Medina, at the age of 20, founded a group that has already turned 35 touring the country with hymns like ‘Vicio’ or this ‘Aprendiendo a luchar’ that, in the end, seemed to sing to themselves in their second album in 1991, ‘Ni un paso atrás’: : “¿Dónde estudias, dónde curras, o en una ocupación? Contra el reino del cipote, del dinero y de la cruz”. (“Where do you study, where do you work, or in an occupation? Against the kingdom of the dick, the money and the cross”). Now it may seem almost a childish perrenque, but in the early 90’s they took the Basque Country by storm and it didn’t take them long to release albums non-stop (and, unlike other of these groups, without losing a bit of their DNA along the way).

‘Sarri, sarri’ – Kortatu

It is curious that one of the few songs in Basque (the other, perhaps, being ‘Ilargia’, by Ken Zazpi) that sounds beyond its borders is one that celebrates the escape from prison of Piti and Sarri, two ETA members who escaped from Martutene prison in 1985. That same year, and on the music of the song ‘Chatty Chatty’, Fermín Muguruza and his band made a comical portrait of what had just happened (“Today the radio broadcasters were broadcasting live that they would eat paella, and Piti and Sarri, right under their noses, were plotting it without them noticing”). Years later it was used as a spearhead against Muguruza, but it led to nothing. In fact, it’s still played at weddings of people who don’t know what they’re dancing to. Luckily.

‘Nos quieren detener’ – Boikot

Before Boikot, the group created in 1987 with ska influences, turned to a more supportive and avant-garde type of rock, they had time to release songs like ‘Eskeletos radiaktivos’, ‘Serrindemadriz’ or ‘Karraskal’. But on the verge of their change of style in 2002, the group came out with a song as was usual for them: short, to the foot and without leaving witnesses. Between hymns and trilogies of albums dedicated to Che Guevara and claims almost of demonstrations in ‘Pueblos’ was hidden a little song that spoke against illegal detentions and how the middle class turned a blind eye. Did you want music against the Movida? Boikot were from Madrid and they couldn’t make it any clearer: “Y burgués, tú nunca entenderás, los problemas de la calle no son de los demás” (And bourgeois, you’ll never understand, the problems of the street don’t belong to others).

We could go on here for long hours, video clips, analysis of Platero y tú’s ‘Juliette’ or Barón Rojo’s albums, or even ask ourselves if Def Con Dos deserves to be here. What is clear is that, as it is sold today, it seems as if the vindictive rock never went beyond the anecdote at the bottom of the page, a suburban movement between the Movida and the “Donosti sound”. But the truth is that there were hundreds of groups that shaped a whole generation and who are hardly remembered.

Manolo Kabezabolo, Siniestro Total, Asfalto, Triana, Obús, Mago de Oz, Cicatriz, Tijuana in Blue, Negu Gorriak and many others found a small refuge outside the audiovisual in a television that protected certain groups and annihilated others: it was time for concerts and Tipo stores at a time when, before social networks, this was the best way to be indignant. Guitars, drums, pogo and screams: When will a series in the style of ‘La ruta’?