News

Inside Facebook’s battle against offensive content

- November 28, 2018

- Updated: July 2, 2025 at 5:41 AM

Facebook announced last month that it will begin implementing some new features aimed at helping users keep their feeds clear of bullying and harassment.

One new addition is that users now have the option to ask for a second review of content that has been reported for harassment or bullying. In the past, this option was only available for those reportedly in violation of the platform’s policies regarding sexual activity, hate speech, nudity, or graphic violence.

Now, alleged harassers can ask the moderators for a second review if they feel that their content was unfairly removed.

The changes are welcome, and include things like the ability to quickly delete or hide multiple comments at a time and added protection for public figures.

Still, knowing that the reviewers must look at roughly 10 million pieces of mostly unsavory content, we wonder if the process is getting better at all.

Here’s a bit more about where Facebook is at when it comes to improving the moderation process.

What we know about Facebook’s content review process

In recent months, there has been a ton of coverage on the topic of Facebook’s content moderation. From a RadioLab episode that dove deep into the company’s ever-changing and relatively mysterious policies to Motherboard’s expansive look at the challenges that come with trying to maintain community standards when that community happens to be larger than many countries.

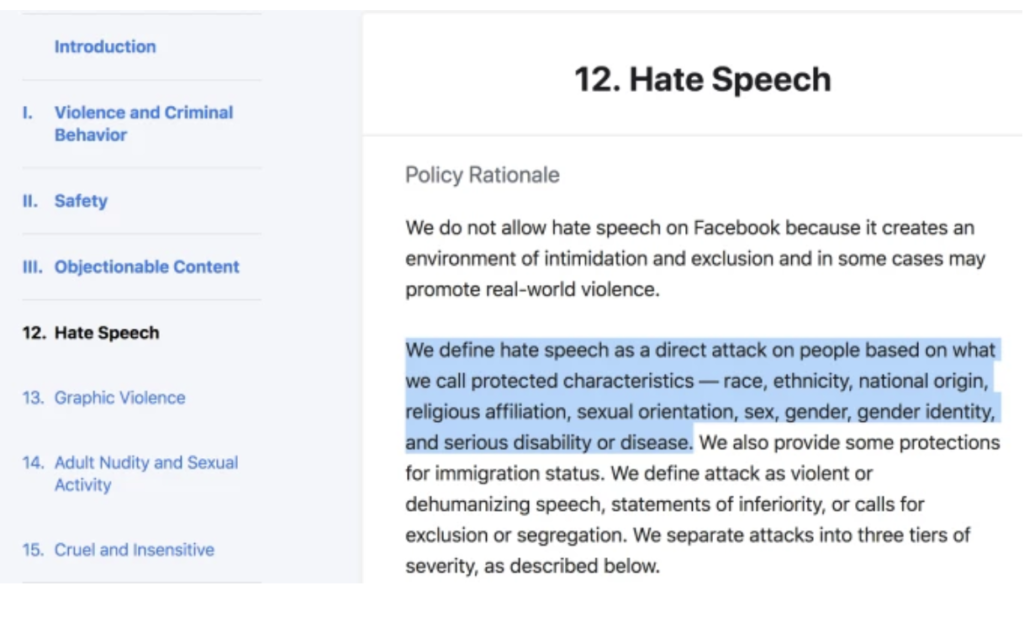

There are 60 people on the Facebook team hired exclusively to write and revise the content moderation policy alone. The policy, in its current form, is a sprawling 27 pages, which aims to balance user safety with free speech.

Within that document, you’ll find a super-specific set of instructions for the company’s team of moderators, and they’re constantly shifting. For example, where nudity is generally a no-go on the site, there are some exceptions to the rule—such as adult nudity in historic Holocaust photos and in some cases, images of certain art pieces.

Facebook also bans terrorist content, non-medical drug use, and hate speech, though content with similar intentions (i.e. offensive speech without the explicit use of a racial slur) can make it onto the platform. A group of 7,500 moderators sifts through flagged posts manually, earning roughly $15 per hour to view what is arguably the worst content on the planet.

But, that might be changing soon.

AI could step in to save the day

After reports came out that content moderators were suffering from PTSD, it’s no surprise that one of Facebook’s primary goals is moderating its content with AI.

While the effort is bound to put some moderators out of a job, the idea is that algorithms will shoulder the burden of filtering through the worst content — reportedly VERY disturbing at times — so humans don’t have to deal with it.

The other benefit for Facebook is, they can once again cover their policies in a shroud of secrecy. Leaked documents, if you remember, have been the reason that any of Facebook’s policies have seen the light of day. Swapping out live bodies for algorithms could mitigate any risk of loose lips sinking ships.

On the flip side, the AI does have some limits. For example, it can only block content that looks like something it has already seen. So new forms of violence from say, a terrorist group might still make it through the filter.

The black and white rules could be on the way out, too

Facebook has long operated in very black and white terms when it comes to determining whether a piece of content violates its rules or not.

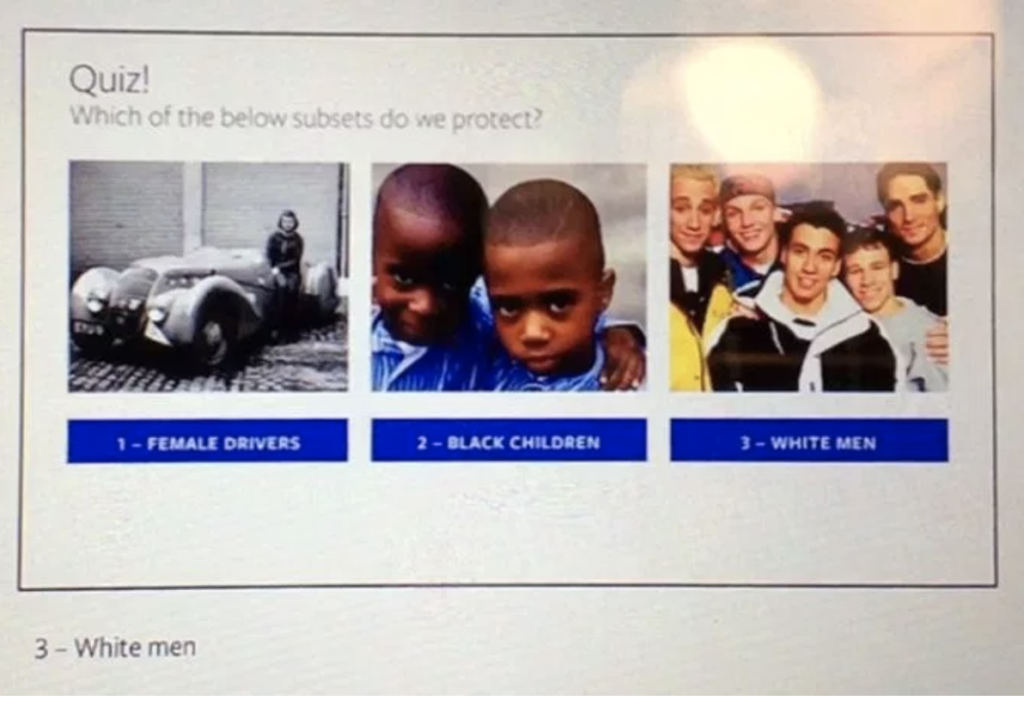

Last year, Facebook’s 25 content moderation guidelines were revealed, among them that controversial protected group quiz— asking “Who do we protect: black children or white men?”

The question was blasted on ProPublica and sparked a great deal of outrage and has since been removed from training materials.

But the rules-based approach has been the source of many problems plaguing the company over the past few years. 2016’s influx of fake news, for example, didn’t contain any nudity or outright hate speech, even though the underlying intent was to generate clicks by way of inciting outrage.

CEO Mark Zuckerberg recently posted that “content that doesn’t explicitly violate the rules” may be reduced. Meaning, the company may curb reach on offensive posts that don’t quite qualify as hate speech. But there is no definitive path forward or broad agreement on what is hate speech and what is not, especially given the wide range of cultural norms that come into play.

Today, we’re looking at issues like people being driven to violence after viewing content on Facebook. Or the platform’s disturbing role in ethnic violence against the Rohingya community in Myanmar. As such, it seems we’ll need to find a solution sooner rather than later.

Zuckerberg is floating the idea of an independent oversight group, a group that would operate as an outside panel of reviewers, much like a Supreme Court. However, some critics feel that this might offload some of the platform’s responsibility.

6 social media apps that are better than Facebook

Read Now ►Wrapping up

In the end, the challenge of moderating Facebook lies in the sheer scale of the platform, and the contextual interpretations spanning cultures across the globe.

And sure, Facebook has done a lot of work to make sure that the policies are enforced on a consistent level, while still allowing for free speech.

That said, Facebook seems to be hinging some hopes on curbing the reach of even some of the most clicked content. Perhaps if we stop rewarding trolls with so many clicks, people may be disinclined to stir up outrage in the first place.

But chances are, Facebook’s content moderation efforts will be an ongoing dilemma.

Grace is a painter turned freelance writer who specializes in blogging, content strategy, and sales copy. She primarily lends her skills to SaaS, tech, and digital marketing companies.

Latest from Grace Sweeney

You may also like

News

NewsFaster creation of cohesive icon systems with Illustrator + Firefly

Read more

News

NewsUbisoft is being criticized for canceling several projects, but it remains focused on its big bet

Read more

News

NewsMany have forgotten about its existence, Xbox continues with the development of this survival saga

Read more

News

News'Return to Silent Hill' has been a flop, but its director says that fans still want more

Read more

News

NewsBen Kingsley was going to have his own separate project in Marvel… until he joined 'Wonder Man'

Read more

News

NewsIt is possible that 'Highguard' may seem like a failure, but in its study, they see it very differently

Read more