Hear the name “Napoleon Bonaparte” and it will immediately evoke an image: The stubby little Frenchman (though he was actually 5’7″) with the black bicorne and a hand tucked into his coat. He’s either heroically perched atop his famous white horse, Marengo, or sitting proudly in a military tent. Think about him a few seconds longer and you may recall some distant victory over the long-forgotten Prussian Empire, or his rise to power and ultimate failure at Waterloo.

‘Napoleon Bonaparte was a military genius’ has been so overstated that the phrase hardly bears any meaning anymore; certainly not now, over 200 years after his death in 1814. In 1796-1802 the French won 33 of their 51 battles – a 65% success rate.

Once Bonaparte was in charge, the French won 17 out of their 18 battles, a 94% success rate.

So then what was it that made Napoleon so successful? What are these alleged strategies that put him down in history? How did this “country bumpkin from Corsica” evolve into the “God of War” that Prussian General Clausewitz (a man who disliked Bonaparte) titled him?

“I found the crown of France in the gutter and I picked it up.”

It’s impossible to talk about how Bonaparte revolutionized warfare without talking about the man himself. His father, Carlo Buonoparte, was a representative to the court of Louis XVI and a Corsican representative. During the French conquest of Corsica, Carlo embraced the new French government wholly, a move Napoleon would deem traitorous and for which he never forgave him.

A Corsican patriot, Napoleon attended military university but loathed it. At the time of his schooling, it was virtually impossible for a talented tactician (which he thought himself to be) to get the opportunity to lead without a noble upbringing and a powerful financial backing.

All that changed after the French Revolution, and the broken, scattered France that came as a result was one searching desperately for a beacon. Napoleon Bonaparte was determined to be that leader.

“History is a set of lies agreed upon.”

Much of Napoleon’s fame was built off the battlefield. Bonaparte strove to become ‘the man, the myth, the legend,’ even if he had to lie to do it. Bonaparte was the master of presenting himself in a positive light: ‘The tactician without peer, the leader of men and the conqueror of Europe.’ He did this by masterfully spinning the story to favor himself even if the reality was far more grim. He wrote and spoke eloquently, and regularly commissioned paintings, sculptures, and even currency of himself to reinforce to the public that he was not a soldier but a sovereign, not a dilettante but a divine.

“Soldiers generally win battles; generals get credit for them.”

As early as the Siege of Toulon – his first battle – Napoleon made it a point to inspire loyalty and courage among his men – a talent that would serve him well for the entirety of his career. Unlike his military contemporaries, Napoleon opted to lead from the front of the charge, not the back – proving to them that he was willing to die for victory. This blatant selflessness was unheard of from a military commander, and his other men were inspired to follow; they’d never seen anything like him.

At the Siege of Toulon, Bonaparte’s first offensive, he had his horse shot from under him and he himself was stabbed through the thigh by a bayonet – a wound that could have killed him. Bonaparte brushed it off, sallied forth, and led his men to victory. His regiment was stunned by his dedication and perseverance and subsequently flocked to him.

“A leader is a dealer in hope.”

Bonaparte was an avid admirer of famous military captains of the past, including Alexander the Great, Gustavus Adolphus, and especially Frederic the Great. “Read over and over again the campaigns of Alexander,

Hannibal, Caesar, Gustavus, Turenne, and Frederic the Great,” he wrote. “This is the only way to become a great general…”

No famous leader comes from nothing, and the inspiration he took from these influences was first imitated and later improved; Napoleon’s ability to see strengths and weaknesses in his enemy line and his own was very reminiscent of Alexander. His aggressive style of conduct and extensive use of cavalry was much more indicative of Frederic.

Playing on the offensive was a cornerstone of Napoleon’s strategy: Only three times during the course of his career did he play defensively: The battles of Leipzig, La Rothière, and Arcis in 1814. Even on those occasions he only took on a defensive stance after his initial attack failed.

“You must not fight too often with one enemy, or you will teach him all your art of war.”

Intel contributed to much of Napoleon’s victories in Europe. His military campaigns actually took place long before any battles began or shots were fired. Bonaparte worked very hard to keep his intentions carefully shrouded from the enemy. He censored newspapers, closed borders, and even detained travelers if he was close to mounting an offensive. This way Napoleon made certain that enemies could not predict his positions or know where he planned to strike. When he did strike, it was on his terms at his choice of location, with overwhelming numbers and superior firepower.

On the other side of the coin, Napoleon always ensured that his scouts and reconnaissance forces frequently alerted him to necessary information about enemy forces, division movements, firepower, battle plans, and even updated maps. This way, he knew areas that would be less defended, as well as when key tactical locations (such as enemy capitals) could be seized.

“Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake.”

Napoleon outlined his military campaigns with the focus being on keeping them short and brutal. This meant angling his troops and goading enemy leadership towards a decisive battle where he believed he had the advantage. Examples of this include his brilliant military ploy at Austerlitz, or the battle of Leipzig. Both battles were meticulously engineered by Napoleon with designated defensible positions, lures for the enemy, and flanking divisions all prepared to strike at their commander’s word.

By minimizing the number of battles fought and keeping those battles grandiose and lightning-fast, Bonaparte often obliterated huge chunks of the opposition in a matter of hours. The remainder of the military campaign would be far simpler with so much territory gained, reinforcements acquired, and enemy morale crushed. When it came to ground tactics there were three major variants Napoleon employed: Maneuver to the rear, central position, and ordre mixte.

“Ability is nothing without opportunity.”

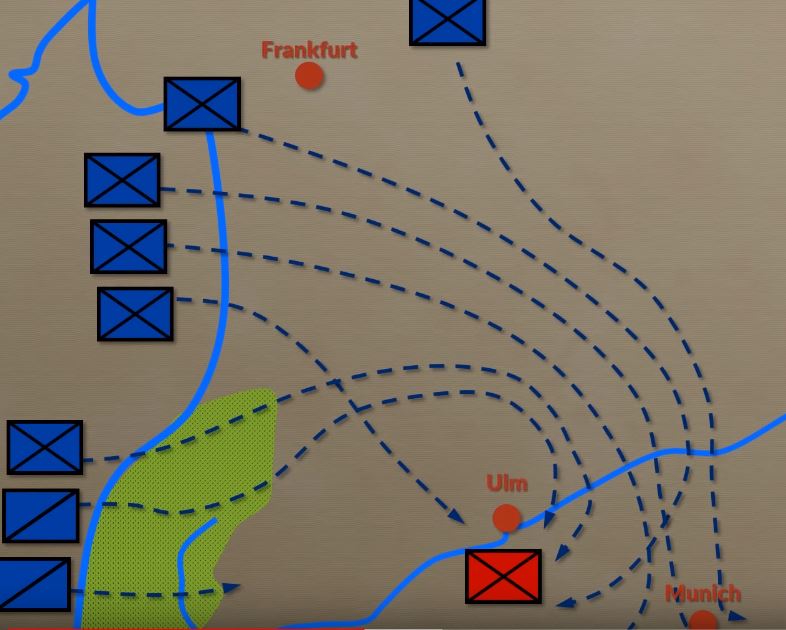

Maneuver to the rear: Napoleon did not invent the classic flank, but he made extensive use of it – at the most opportune moments. He used this technique both in live combat and in broader military strategy: In broader terms, he would often use a flanking maneuver to sever the enemy’s path to their fallback line, eliminating their escape route. This left the enemy with the choice to retreat the city before the flank took hold, or be forced to face attack from both sides.

In the heat of battle (like at Austerlitz) Bonaparte would lure enemy battalions into susceptible positions by deliberately leaving a poorly-defended angle in his own line. The enemy would fall for the trap, and he would send his Imperial Guard to flank, riding in on swift cavalry and wreaking havoc.

“The battlefield is a scene of chaos. The winner will be the one who controls that chaos.”

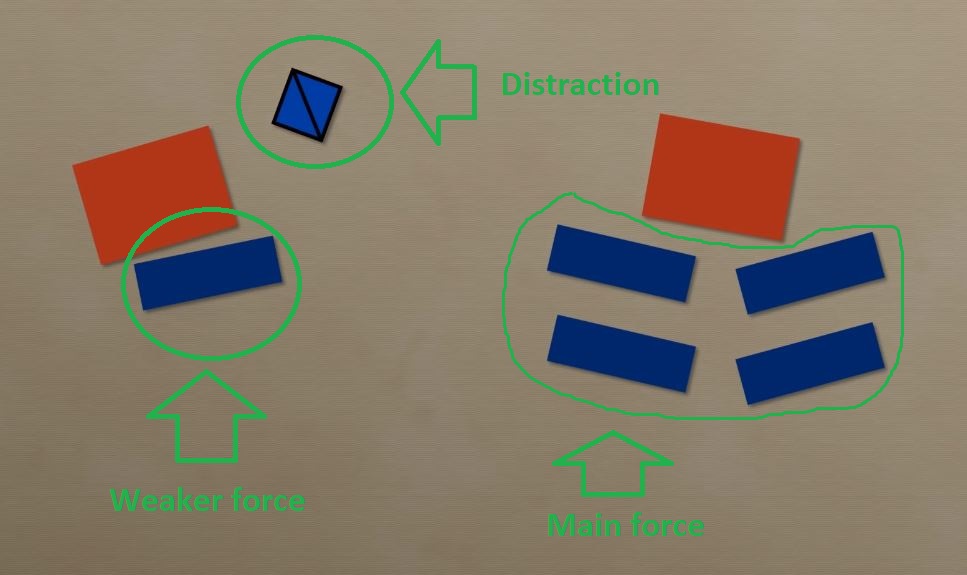

Central Position: This maneuver was done to keep enemy forces divided. It carries with it a larger risk, as the enemy is now able to fire upon you from either side. The goal is to send few reinforcements forward – ideally ones that are fast and expendable.

While the enemies on either side fire upon these, the remainder of the forces attack all together at the divided enemies, catching them by surprise. After one side was killed or forced to retreat, Bonaparte’s victorious troops would quickly hurry to pile on the attack against the remaining side. This way he distracted, then defeated in detail.

Top 5 political speeches of all time

Read Now ►“Impossible is a word only to be found in the dictionary of fools.”

Third, Bonaparte’s military composition allowed him to perform maneuvers that his contemporaries could only dream of. His revolutionary ‘Ordre Mixte’ has been modeled after long since, and remains the general composition of modern units and divisions even today. Napoleon focused on small effective formations of varying soldiers, talents, and equipment, rather building massive armies. He then put these mixed divisions in positions where they could be most effective:

The formation was lines of riflemen in the center to focus firepower. This rain of bullets also prevented Napoleon’s opponents from using the aforementioned Central Position strategy. Next were powerful columns on either arm of the center lines to discourage flanking and provide support to both the center line and allow for flanking opportunities of his own against any opponents foolish enough to try and close in. High-mobility cavalry were sent in at opportune moments, while constant barrages of artillery sewed confusion, noise, and cover for them.

“Riches do not consist in the possession of treasures, but in the use made of them.”

The French army was so strong under Bonaparte’s leadership not because of any one outstanding feature or squad (such as Genghis Khan’s horsemen archers or the mighty British navy), but rather because of the way Bonaparte was able to use all the branches in tandem with each other to create overwhelming force. His use of small divisions rather than giant armies meant that major elements of the French army were able to act independently, no matter what stage of the battle plan they were on. It also meant that any one division was seldom caught unprepared.

“Great ambition is the passion of a great character.”

Napoleon’s reputation is attributed to his innate natural talents to raise his troops’ morale, accurately gauge the strengths and weaknesses of the enemy both on the field and off, and an aggressive style of waging war. In terms of military might, Bonaparte put exceptional focus on information superiority: Keeping his movements shrouded in secrecy while making it a priority to know the enemy’s every move. This combined with his smaller divisions of combat allowed his armies to move quicker and smarter.

Napoleon Bonaparte remains one of the greatest military commanders in history, and his wars and campaigns are still studied at military schools worldwide to this day. His political and cultural legacy has endured as one of the most celebrated and controversial leaders in human history.

Top 5 non-political speeches of all time

Read Now ►