How To

Stan Lee masterclass: How to create a good villain

- December 20, 2018

- Updated: March 7, 2024 at 5:37 PM

“There’s no such thing as a villain,” Stan Lee claimed with a cryptic smile. Coming from the man who created the Green Goblin, Dr. Doom, Venom, Magneto, and a staggering surfeit of other mischievous malefactors and wretched wrongdoers, this may seem like an exercise in hypocrisy. When you’re telling a superhero story, the good guy’s got to have a bad guy to go up against. Doesn’t every film in the Marvel Cinematic Universe have an antagonist for the hero to face off against? What about Loki for Thor? Whiplash for Iron Man? Killmonger for Black Panther? What about Thanos? Can we really say these characters aren’t villains?

How Stan Lee created some of pop culture’s greatest villains

“[They] may be viewed by you, me, and the general populace as dirty, rotten scoundrels and vile villains,” Stan Lee said, “but – and here’s the takeaway – they don’t see themselves as villains! Each and every villain in comics, in movies, in novels – and especially in real life – thinks of him or herself as the good guy. He’s the hero of his own story.”

‘History is written by the victors’ and the late Stan Lee took pride in reflecting as much in his writing. For sure, the villain is cast in an ugly light, and it’s because he or she is the one going up against our hero.

But what made Stan Lee’s villains so different was that acting against the protagonist did not disqualify them from having real character arcs: Driving motivations, emotions, goals, internal conflict, and tragic backstories of their own.

“The school bully wants your lunch money because he feels like he’s misunderstood and picked-on himself and he’s fighting for all the picked-on people in the world,” Lee said. “They and only they know what’s right and they and only they have the guts to do what needs to be done.”

Real villains of the world aren’t evil for the sake of being evil. Rather they act with goals in mind and seek to achieve them by whatever means necessary. If the cost is steep, the ‘bad guy’ deems it a necessary casualty in order to accomplish a greater good. “No one ever thinks ‘I’m about to do an evil thing, even if I have another option,'” Lee said. “We humans are champions at rationalization, at convincing ourselves that we’re doing the right thing, no matter how we must twist logic to get to that conclusion.”

Magneto isn’t killing humans because he’s simply evil; he’s doing it because mutants are discriminated against and he wants to promise their safety. Kingpin runs a ruthless mob through Hell’s Kitchen because he believes it’s the only way to maintain a semblance of order in an otherwise chaotic city. Killmonger asserts that he will do take Wakanda to its rightful position as a global ruler, looking after those oppressed and in need.

Black Panther

Watch Black Panther Now ►The villain needs to be a person

Giving the villains of his comics empathetic motivations and real personalities that weren’t just ‘comic book villain’ was what set Lee’s characters apart from the competition. We as readers can certainly dream of flying, lifting tall buildings, firing lasers out of our eyes, or lifting objects with our minds, and that’s the fun of reading superhero comics. Of course, we have no way of actually doing these incredible things. Jealousy, fear, anger, resentment, the desire for revenge, though; these are familiar emotions, and strike closer to home.

“Sure your hero might be extra strong or might be able to fly or run as fast as a comet. But unless you care about the hero’s personal life, you’re just reading a shallow story,” confides Lee. “And just because the guy’s got a superpower doesn’t mean he hasn’t got the same problems that you or I might have! Maybe he doesn’t have enough money. Maybe he has a family problem. Maybe the girl he loves doesn’t love him.”

“I like to get villains who have some sort of a background so we know about their personal life – just like I like to know the personal life of my heroes,” Lee said.

Instead of aiming for a simple binary black vs. white heroes vs. villains, Stan Lee opted to make his antagonists’ issues relatable, even if their solution to these issues was typical diabolical behavior, like robbing a bank or kidnapping someone. “Even though what you’re writing amounts to a fairy tale for grown-ups, try to keep enough facts and try to give enough detail that the reader will say ‘well, it could have happened!'”

How Stan Lee created Marvel’s complex characters

Read Now ►Bring out the hero’s best qualities

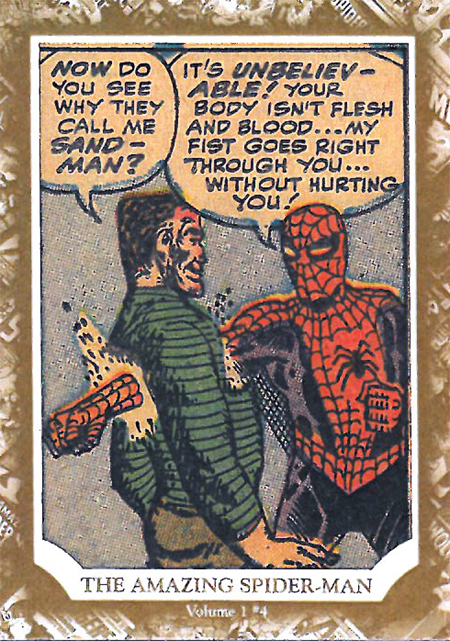

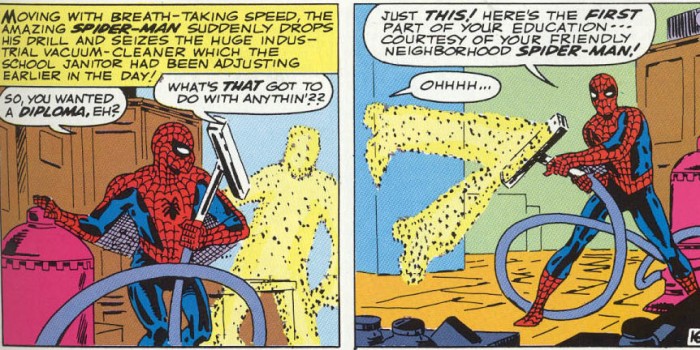

Since his villains had sympathetic problems, Stan Lee’s characters were often presented as believable foils to their counterpart hero in some way, serving to highlight his or her weaknesses and strengths. This similarity in personality or issue forced the hero to address and power through their shortcomings, and to do so in the proper way, unlike the bad guy. Spider-Man and Venom are classic examples of this:

Both Peter Parker and Eddie Brock fell victim to the same alien symbiote, a suit that granted its wearer incredible strength, durability, speed, and power. However, it did so at the cost of the wearer’s personality and self-control.

Eddie Brock gave in to his love for power, gave in to his addiction to the suit and the high it gave him to wear it. Peter Parker, the hero of the story, fought back against the symbiote after seeing the damage it was doing to people he cared about. Any reader can enjoy a good power trip looking at pictures of Venom going on a rampage, but it’s clearly Peter Parker who demonstrated stronger willpower, more maturity, and a strong moral compass.

Write your villain with your hero in mind

Venom is also a good example of a baddie that’s more than a match for the hero of the story. “The first thing you have to do is get a villain who seems to be unbeatable by the hero. That makes your job tougher because the hero has to beat him in the end.” Villains need to suit their heroes, and provide a solid counterpoint to their powers and, more importantly, their personality.

The good guy needs to match the bad guy. Look at Batman and Joker, or Punisher and Kingpin. “Would you have Robocop fighting giant alien flying jellyfish or a house-haunting apparition?” Lee exclaimed. “Of course not! Those aren’t the kind of opponents Robocop squares off against.”

Every hero needs a suitable challenge; succeeding against all odds makes for a far grander (and more exciting) story than simply pummeling a few thugs and sending them to jail. Abomination wouldn’t be a great pick for a superhero like Captain America, but he’s great against Hulk!

Stan Lee made it a focal point in his narrative to introduce new villains that provided a real threat to the hero. “You can’t know how heroic or resourceful your hero is unless he goes up against someone who is not just his equal in power or determination or intellect,” says Lee, “but up against someone faster, stronger, smarter, and more ruthless!

“In the beginning, writing the hero is very exciting, but once you’ve created the hero, you’ve got him. And he’s going to be pretty much the same in every story,” Lee said. “But each story needs a new villain. So it is more interesting to keep coming up with new villains because each one is a new problem.”

“Villains are the most important people in the story”

The hero has no choice but to become predictable. Every protagonist has a personality, relationships with other characters, a tried-and-true method for solving his problems, and (if they’re the rough-and-tumble, Hitler-punching type) a specific style of combat and a striking visual aesthetic. Day in, day out that can get dull to read, even for the best of heroes.

“That’s only natural,” Lee said, “because we’ve had time to get to know him, to learn to anticipate his reactions.” That hero needs an antagonist to shake up the formula, to introduce some needed chaos to the mix. “Our villain has to be unique, clever, inventive, and full of fiendish surprises.”

Adversity shapes us into stronger people, and that adversity comes in all shapes and sizes. The same goes for the antagonists of Stan Lee’s works. Sometimes Tony Stark went toe-to-toe with big bad dudes like Thanos or Ultron, but other times it was Obadaiah Stane, an executive on his own company’s board. Other times Stark was fighting with his own inner demons – his paranoia or his alcoholism.

Stan Lee considers this raising the bar for the hero. “Villains have a great responsibility that comes with their great power: They have the responsibility to make you, the reader, believe that the hero doesn’t stand a chance against them.” When all seems lost and things seem hopeless, that’s when the protagonist has to rise up and meet the challenge.

Peter Parker wins. Not Spider-Man.

What’s more important than the monster of the week is how the hero defeats it. It’s easy to say Spider-Man punches his way through a group of thugs, but what does that give us other than some popcorn-munching theatrics and flashy visuals? Looking deeper, there has to be a moral behind why the good guy succeeds. What lesson can be learned? On what part of the hero’s skill should this issue capitalize? Maybe it’s their bravery. Maybe it’s their ability to coordinate a team. Or their persistence and dogged determination:

Presenting challenging monsters and showing how to conquer them is a cathartic way of coming to terms with our fears and finding the internal strength to surmount them. Lee credits this catharsis as one of the chief reasons audiences love superhero stories.

By showing the hero defeating the scary monster we see that “the superhero – the absolute pinnacle of human nobility and virtue – takes on the monster – the physical manifestation of humanity’s irrational fears. If they can beat it, you can too.” To emphasize that the reader too could triumph over his difficulties, Stan Lee seldom had his heroes win fights through brawn. Instead, most of Lee’s heroes were smart: Reed Richards, Bruce Banner, Peter Parker, or Stephen Strange. Their smarts were how they won the fights, not their superpowers.

Stan Lee showed his readers that while superpowers were fantastic, fun, and marvelous, the heroes didn’t need them conquer their fears.

In the end, the antagonists that Stan Lee created were so successful not because of their bulging biceps, exorbitant wealth, or their mighty superpowers. Quite the opposite: It was because they were more believable, more relatable, and more human. This closeness makes them both more empathetic, but also more frightening; seeing yourself in both the hero and the villain of a story is like listening to the angel and devil arguing on your shoulders – both voices are a part of you, and it’s up to us to know which path is the right one, even if the wrong path can seem awfully tempting. But that’s what resisting that bad side of you does: It means you get to play the part of the hero.

You may also like

How to see the price per hour you pay for your Steam games

Read more

Shopping in ChatGPT: here is how it works

Read more

Tesla Faces Brand Perception Crisis Amid Consumer Skepticism

Read more

Electric Vehicle Sales Plummet Nearly 40% at Ford Despite Overall Sales Surge

Read more

Tesla Discloses $2.4 Million Transactions with SpaceX and Other Musk Ventures

Read more

What is DLSS?

Read more